Scientists Reveal Cognitive Mechanisms Involved in Bipolar Disorder

An international team of researchers including scientists from HSE University has experimentally demonstrated that individuals with bipolar disorder tend to perceive the world as more volatile than it actually is, which often leads them to make irrational decisions. The scientists suggest that their findings could lead to the development of more accurate methods for diagnosing and treating bipolar disorder in the future. The article has been published in Translational Psychiatry.

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a chronic affective condition characterised by alternating episodes of extreme elation (mania) and severe depression. According to the WHO, an estimated 40 million people worldwide live with bipolar disorder, but diagnosing the condition can be challenging, as its symptoms are not always apparent.

Studies show that individuals with bipolar disorder, even during remission, exhibit specific behavioural and brain activity patterns that may indicate the condition. In particular, patients with bipolar disorder have been found to exhibit impairments in their decision-making processes. Normally, when making a decision, a person tries to choose the option that offers the greatest reward. If the choice proves to be correct, they are likely to make the same decision again next time. However, circumstances can change, requiring a person to reassess which option offers the greatest benefit. Patients with BD often struggle to recognise when it is necessary to adjust their decision-making strategy.

A group of researchers from HSE University, Sechenov University, the Max Planck Institute, and Goldsmiths, University of London, conducted an experiment to investigate how individuals with bipolar disorder adapt to environmental changes and make decisions.

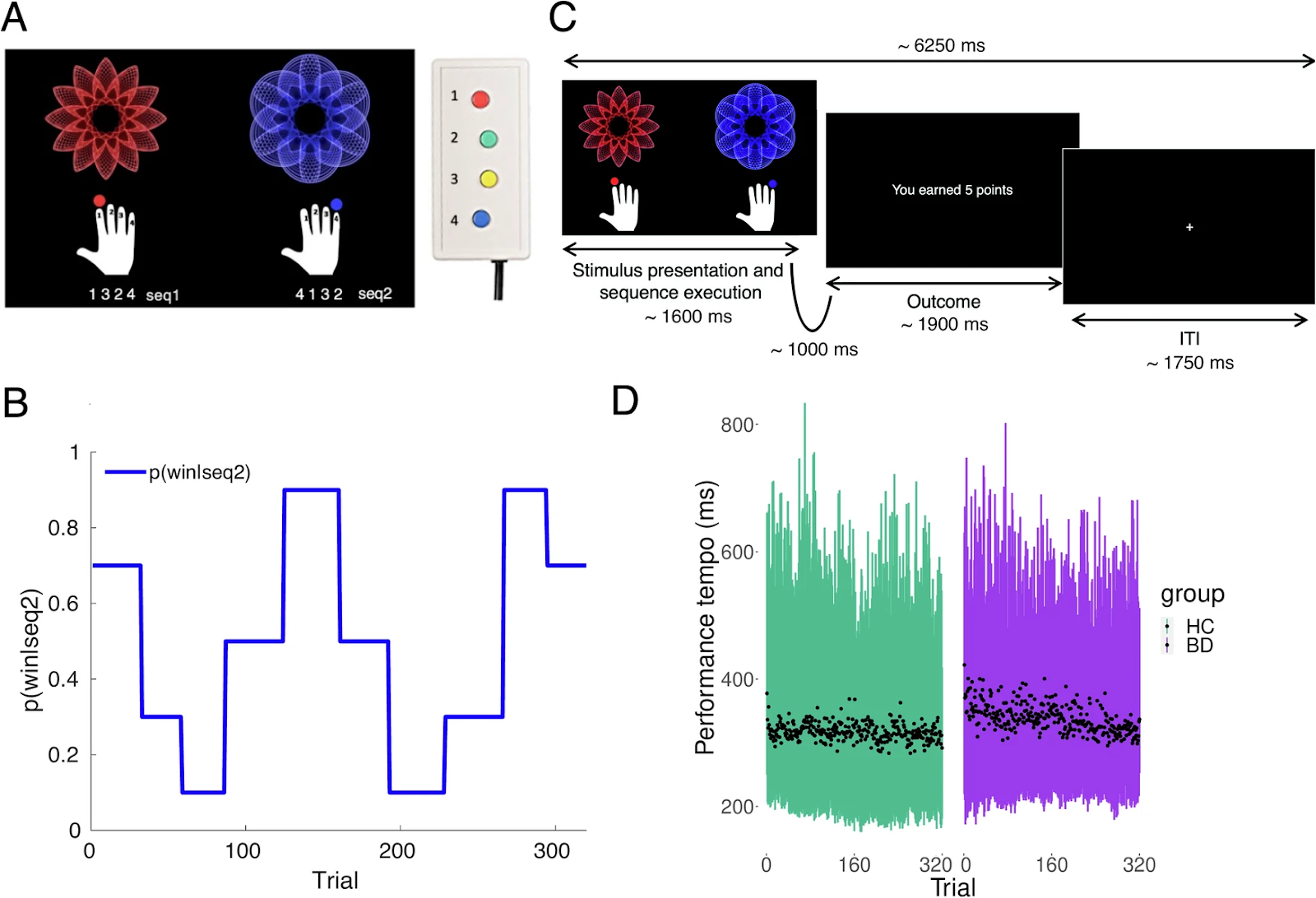

The study included 22 bipolar patients in remission and 27 healthy volunteers who served as the control group. Participants were instructed to earn as many points as possible by selecting either a blue or red image on a computer screen. Each option had a certain probability of winning, which changed throughout the experiment. For example, initially the blue image won 70% of the time, but later its winning probability dropped to 30%. Throughout the experiment, participants’ neuronal brain activity was monitored using magnetoencephalography (MEG).

Marina Ivanova

'This experimental design mimics real-world conditions, which are also full of uncertainties and require constant decision-making—even in everyday situations. For example: should you pet a cat, or is it better not to? Will it purr or scratch? We try to anticipate the consequences of our choices and make the best decision accordingly,' explains Marina Ivanova, Junior Research Fellow at the HSE Institute for Cognitive Neuroscience and primary author of the study.

The results of the experiment showed that participants with bipolar disorder perceived the environment as more volatile than it actually was, which often led them to make incorrect choices.

'If a person makes a decision and it turns out to be the right one, they will likely repeat that choice next time. However, someone with bipolar disorder may change their strategy even after a successful outcome,' says Ivanova.

The scientists also observed neural differences in brain regions involved in decision-making, specifically the medial prefrontal, orbitofrontal, and anterior cingulate cortices. At the neural level, while healthy individuals exhibited alpha-beta suppression and increased gamma activity during the experiment, participants with bipolar disorder showed dampened effects.

'Our study reveals that even outside of manic or depressive episodes, people with bipolar disorder process information about environmental changes differently. They constantly anticipate changes but struggle to properly learn from them when they occur. As a result, their decisions are more spontaneous and unpredictable than those of the control group,' comments Ivanova. ‘However, it is important to remember that our experiment only simulates real life, so we should be cautious when applying these findings to actual everyday situations.'

The results may be useful for developing models to diagnose bipolar disorder and predict its recurrence. In the future, this approach could be adapted to other mental health conditions involving adaptive learning impairments and may also serve as an important step toward advancing computational psychiatry.

See also:

HSE Researchers Determine Frequency of Genetic Mutations in People with Pulmonary Hypertension

For the first time in Russia, a team of scientists and clinicians has conducted a large-scale genetic study of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. The team, which included researchers from the International Laboratory of Bioinformatics at the HSE Faculty of Computer Science, analysed the genomes of over a hundred patients and found that approximately one in ten carried pathogenic mutations in the BMPR2 gene, which is responsible for vascular growth. Three of these mutations were described for the first time. The study has been published in Respiratory Research.

HSE Scientists Reveal How Disrupted Brain Connectivity Affects Cognitive and Social Behaviour in Children with Autism

An international team of scientists, including researchers from the HSE Centre for Language and Brain, has for the first time studied the connectivity between the brain's sensorimotor and cognitive control networks in children with autism. Using fMRI data, the researchers found that connections within the cognitive control network (responsible for attention and inhibitory control) are weakened, while connections between this network and the sensorimotor network (responsible for movement and sensory processing) are, by contrast, excessively strong. These features manifest as difficulties in social interaction and behavioural regulation in children. The study has been published in Brain Imaging and Behavior.

Similar Comprehension, Different Reading: How Native Language Affects Reading in English as a Second Language

Researchers from the MECO international project, including experts from the HSE Centre for Language and Brain, have developed a tool for analysing data on English text reading by native speakers of more than 19 languages. In a large-scale experiment involving over 1,200 people, researchers recorded participants’ eye movements as they silently read the same English texts and then assessed their level of comprehension. The results showed that even when comprehension levels were the same, the reading process—such as gaze fixations, rereading, and word skipping—varied depending on the reader's native language and their English proficiency. The study has been published in Studies in Second Language Acquisition.

Mortgage and Demography: HSE Scientists Reveal How Mortgage Debt Shapes Family Priorities

Having a mortgage increases the likelihood that a Russian family will plan to have a child within the next three years by 39 percentage points. This is the conclusion of a study by Prof. Elena Vakulenko and doctoral student Rufina Evgrafova from the HSE Faculty of Economic Sciences. The authors emphasise that this effect is most pronounced among women, people under 36, and those without children. The study findings have been published in Voprosy Ekonomiki.

Scientists Discover How Correlated Disorder Boosts Superconductivity

Superconductivity is a unique state of matter in which electric current flows without any energy loss. In materials with defects, it typically emerges at very low temperatures and develops in several stages. An international team of scientists, including physicists from HSE MIEM, has demonstrated that when defects within a material are arranged in a specific pattern rather than randomly, superconductivity can occur at a higher temperature and extend throughout the entire material. This discovery could help develop superconductors that operate without the need for extreme cooling. The study has been published in Physical Review B.

Scientists Develop New Method to Detect Motor Disorders Using 3D Objects

Researchers at HSE University have developed a new methodological approach to studying motor planning and execution. By using 3D-printed objects and an infrared tracking system, they demonstrated that the brain initiates the planning process even before movement begins. This approach may eventually aid in the assessment and treatment of patients with neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s. The paper has been published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

'Biotech Is Booming Worldwide'

For more than five years, the International Laboratory of Bioinformatics at the HSE Faculty of Computer Science has been advancing cutting-edge research. During this time, its scientists have achieved major breakthroughs, including the development of CARDIOLIFE—a unique genetic test unmatched worldwide that predicts the likelihood of cardiovascular disease. With the active participation of HSE students, including doctoral students, the team is also working on a new generation of medicines. In this interview with the HSE News Service, Laboratory Head Maria Poptsova shares insights into their work.

Civic Identity Helps Russians Maintain Mental Health During Sanctions

Researchers at HSE University have found that identifying with one’s country can support psychological coping during difficult times, particularly when individuals reframe the situation or draw on spiritual and cultural values. Reframing in particular can help alleviate symptoms of depression. The study has been published in Journal of Community Psychology.

Scientists Clarify How the Brain Memorises and Recalls Information

An international team, including scientists from HSE University, has demonstrated for the first time that the anterior and posterior portions of the human hippocampus have distinct roles in associative memory. Using stereo-EEG recordings, the researchers found that the rostral (anterior) portion of the human hippocampus is activated during encoding and object recognition, while the caudal (posterior) portion is involved in associative recall, restoring connections between the object and its context. These findings contribute to our understanding of the structure of human memory and may inform clinical practice. A paper with the study findings has been published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

Researchers Examine Student Care Culture in Small Russian Universities

Researchers from the HSE Institute of Education conducted a sociological study at four small, non-selective universities and revealed, based on 135 interviews, the dual nature of student care at such institutions: a combination of genuine support with continuous supervision, reminiscent of parental care. This study offers the first in-depth look at how formal and informal student care practices are intertwined in the post-Soviet educational context. The study has been published in the British Journal of Sociology of Education.